Division of Power within NYC

One of America’s governing characteristics is that it is ruled with a federal-state-local division of political authority, a system known as federalism. For New Yorkers, “local” means yet another division of power: city-borough-district. Despite its drawbacks, dividing the city’s operations on these levels is worth it to ensure that our government is democratic.

At first glance, New Yorkers may be outraged at the duplication of operations between three local levels of governance and even the repetition within each level. This separation of power leads to inefficiency, bureaucracy, double spending, and difficulty in knowing who to reach out to about issues. Who should I send my educational proposals to: the PTA or leadership of an individual school; the Community District Education Council or superintendent on the district level; the Department of Education borough office; or the Department of Education citywide office, not to mention the state Department of Education and federal Department of Education? The complexity of this organization of power seems unnecessary. It seems silly to have office after office that claims to do similar tasks, except on different scales. News outlets love to point out these offices and their expenditures, claiming they waste taxpayer dollars on tasks that could have been done by their parent organization.[1] While there is no doubt that the city could function with only the citywide Department of Education, the question is whether it should.

The question of division of power is an old one, dating back to the Roman Empire, which succeeded in part because of its flexibility in allowing conquered peoples to continue ruling themselves locally, at least to a certain degree. It is a question debated during the American Revolution, the formation of New Amsterdam, and the Act of Consolidation. One reason for division of power is to prevent any one person or department from having too much power.[2] Fearing an overpowering federal government, Antifederalists pushed for states’ rights. The Dutch in New Amsterdam divided power between two burgomasters and many aldermen so that one burgomaster would not acquire too much power. And, the Act of Consolidation—which merged Brooklyn, Queens, and Staten Island with Manhattan and the Bronx in 1898—created the borough presidents so that the mayor would not control everything. The division of power in NYC among many bureaucracies allows for processes to be more democratic, aided by the wisdom of the crowd, and less prone to abuse of power.

Another reason for division of power is to protect the little guy (districts) from tyranny of the majority (an oppressive city). Madison warned of tyranny of the majority in Federalist No. 10. To ease Brooklynites’ fear that a loss of autonomy to New York would mean second-class treatment, the borough president was created in the Act of Consolidation. However, a century later, Manhattan still rules the outer boroughs in many respects (1:12.3 land ratio) as tiny England ruled the vast United Colonies (1:8.6 land ratio) in the 1760s. Manhattan’s problems have often been placed above those of the outer boroughs because Manhattan provides for 74% of the city’s GDP and, as such, a majority of tax dollars and lobbying. John Lindsay was blatantly Manhattan-centric when he only cleared snow in Manhattan (although not much) after the severe snowstorm of 1969.[3] The majority in “tyranny of the majority” is based on political might, not just population. As another example, tyranny of the majority occurred in the repeated proposals to shut down City Island’s fire station despite the slower response of nearby fire stations.[4],[5] Although the shutdown never occurred, the repeated willingness of citywide politicians to do so trampled on the residents of tiny City Island, who lack political clout as a small number of voters.[6] Borough and district positions protect against tyranny of the majority. Officials and agencies on the borough and district level advocate for local needs, acting as the bottom-up of what would otherwise be an exclusively top-down government.

Local positions are also needed because of NYC’s sheer size and heterogeneity. Since NYC boroughs alone are more populous than most American cities, and NYC varies significantly from place to place culturally, economically, and ethnically, it is hard for citywide policy to be “one size fits all.” Also, despite the domination of the Democratic party, there are countless flavors of Democrats, each with their own views on issues and priorities for resource allocation. Borough presidents can address issues specific to their borough without the delay or contention from involving the rest of the city. To demonstrate, Ruben Diaz revitalized public housing in the Bronx, and Scott Stringer worked to make Manhattan an entrepreneurial hub.[7] Both addressed local concerns much faster than City Hall could have responded. Flexibility from the division of power onto sublocal levels makes addressing local concerns easier.

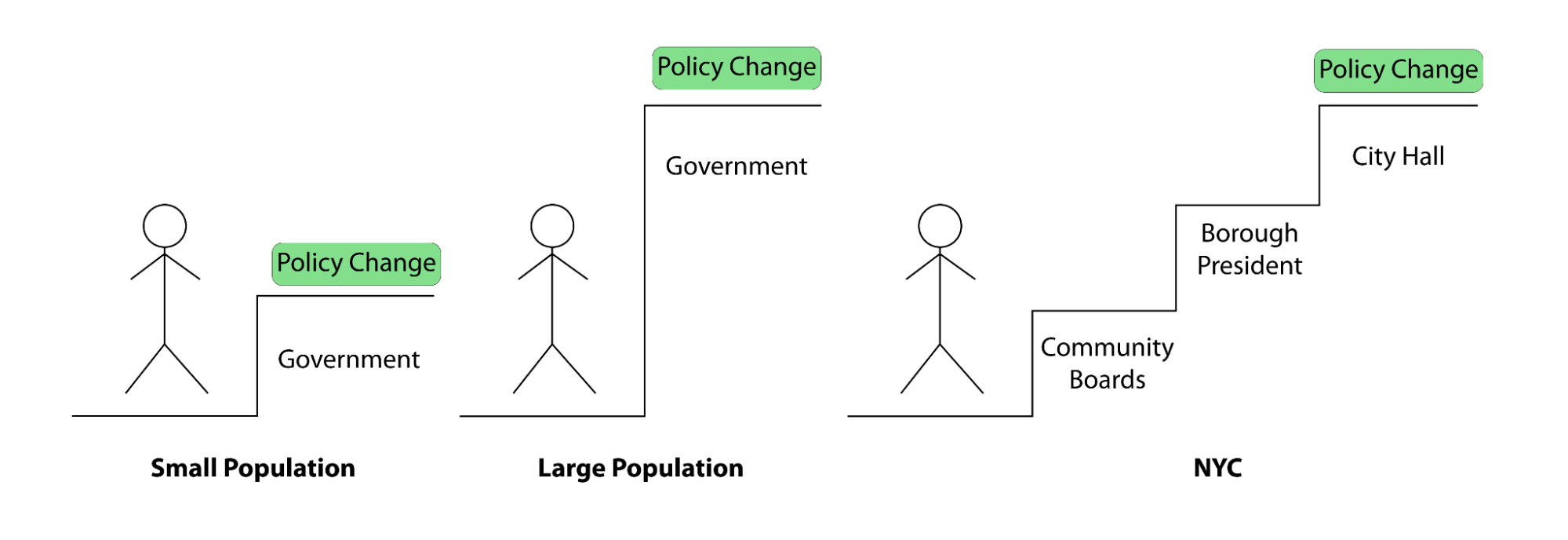

In a democracy, citizens should be able to bring concerns to their government easily. The steps a citizen has to take to effect policy change can be thought of as a jump, illustrated in the figure below. In a town of 20,000 people, the jump is small, so no division of the local government is needed. But for a large population, the jump is too big for an individual to make in one step. In NYC, with 8 million people, this is analogous to reaching out to the mayor or City Council directly. Although council members claim to want to help constituents, they tend to respond to individuals only if they are large donors or community leaders.[8] NYC solves this problem by dividing the local government into manageable intermediary steps that an individual can take to the top, where policy change ultimately occurs. Community boards hear the concerns of individual residents, the borough president listens to requests from the community board, and City Hall legislation is often brought forth from the borough presidents’ offices. Community boards also sway council members more than an individual does. The steps enable change to ascend, making the government more democratically accountable.

As Churchill said, while democracy is not perfect, it is the best form of government that we have. Although “federalism all the way down” leads to higher spending and trivial-looking offices that are not essential to the functioning of the city, this organization of government helps slow down corruption, protect the interests of the most New Yorkers, allow for flexible government action in different regions, and lower the barrier for change.

Citations

any. Accessed 15 Oct. 2023.

Comments